What matters when optimizing a web application

Picture the scenario - you’ve inherited a web application and been asked to make it scale to serve a larger number of concurrent users. You don’t have the option of re-writing it in your favourite whizz-bang language or framework, so how should you go about improving performance?

I’ll create an example here using python and flask, but the same principles will hold true in most languages and frameworks. Here is the simple demo app:

import time

import json

import random

import numpy as np

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route("/io")

def io_bound_request(min_response_time=0.1, mean_response_time=0.3, std_response_time=0.2):

io_call_time = np.random.lognormal(np.log(mean_response_time), std_response_time)

wait_time = min_response_time + io_call_time

time.sleep(wait_time)

return "ok!"

@app.route("/cpu")

def cpu_bound_request(min_size=500, max_size=2000):

data = {str(x): x for x in xrange(random.randint(min_size, max_size))}

json.dumps(data)

return "ok!"

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run()

In this simple example we have two endpoints - one that involves a blocking i/o request, and another that is bound by cpu speed. This is common for a web application - some requests can be served using only on memory and cpu, whilst others require calls to a database, or networked cache. We can graph the distribution of their response times

Let’s say 60% of our web requests are CPU bound, and we’ll add an endpoint to help us load test.

@app.route("/")

def make_requests(fraction_io_bound=0.4):

if random.random() > fraction_io_bound:

return cpu_bound_request()

else:

return io_bound_request()

So as a baseline, how many requests per second can our application currently serve? Starting up a single process using gunicorn: gunicorn -b 127.0.0.1:5000 demo_webapp:app

➜ ~ wrk -t 1 -c 1 -d 30 http://127.0.0.1:5000/

Running 30s test @ http://127.0.0.1:5000/

1 threads and 1 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 124.73ms 135.87ms 447.68ms 77.64%

Req/Sec 15.71 22.39 147.00 93.10%

397 requests in 30.08s, 62.42KB read

Requests/sec: 13.20

Transfer/sec: 2.08KB

So that’s 13 requests per second. If we add more concurrent users, performance deteriorates, as each user has to wait for the other user’s request to be processed by the single process. The obvious thing we can do to improve things is to spin up multiple processes. Trying gunicorn -b 127.0.0.1:5000 -w 4 demo_webapp:app

➜ ~ wrk -t 2 -c 20 -d 30 http://127.0.0.1:5000/

Running 30s test @ http://127.0.0.1:5000/

2 threads and 20 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 337.77ms 203.50ms 1.12s 67.07%

Req/Sec 33.65 30.10 190.00 86.21%

1824 requests in 30.10s, 286.78KB read

Requests/sec: 60.59

Transfer/sec: 9.53KB

Using multiple processes gives a linear increase to the number of requests per second we can serve, and in this case allows us to handle 20 concurrent connections. Great! How many processes can we add?

Before we start adding more processes it is worth understanding what is limiting performance. If we hit each endpoint separately we get

➜ ~ wrk -t 2 -c 20 -d 30 http://127.0.0.1:5000/io

Running 30s test @ http://127.0.0.1:5000/io

2 threads and 20 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 1.74s 215.68ms 1.93s 95.54%

Req/Sec 7.42 4.53 20.00 79.12%

336 requests in 30.08s, 52.83KB read

Requests/sec: 11.17

Transfer/sec: 1.76KB

➜ ~ wrk -t 2 -c 20 -d 30 http://127.0.0.1:5000/cpu

Running 30s test @ http://127.0.0.1:5000/cpu

2 threads and 20 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 22.02ms 8.29ms 171.63ms 94.53%

Req/Sec 457.43 63.52 535.00 84.36%

16388 requests in 30.05s, 2.52MB read

Requests/sec: 545.44

Transfer/sec: 85.76KB

The results indicate that the ~20% of requests which i/o bound are having a disproportionate impact on performance. When a process blocks on i/o, the process does nothing while it could otherwise be serving cpu bound requests. We can add more processes, or even threads, to increase the number of requests we can serve, but as long as we have more users triggering these i/o bound requests, our added capacity will soon be tied up, waiting on the blocking i/o calls.

So in an ideal world we would like to have more processes than we have concurrent i/o bound requests, as this would mean we always have remaining processes available to serve cpu bound requests. In the real world we want our servers to be able to handle thousands of concurrent users, and it isn’t practical to spin up thousands of processes on each machine due to the memory overhead of each process. We can use threads, which have a lower memory overhead, but again this means that our ability to serve requests is being limited by the memory overhead of the concurrency technique we choose.

The solution to this problem is to use asynchronous i/o requests. These are essentially threads that are so lightweight that we can spin up thousands per process. In python 2.7 we can use gevent, which monkey-patches our existing code so that the requests are run in co-routines on top of the event loop. When a request blocks on an i/o call, rather than the process waiting, the co-routine yields, allowing our single python process to continue processing other requests. As long as the memory requirements for the co-routine are small, and the i/o requests return reasonably quickly, we can likely handle enough concurrent users so we that we will now be limited by the CPUs capacity to process all the CPU-bound requests. Testing again using gunicorn -b 127.0.0.1:5000 -w 4 -k gevent --worker-connections=2000 demo_webapp:app:

➜ ~ wrk -t 2 -c 100 -d 30 http://127.0.0.1:5000/

Running 30s test @ http://127.0.0.1:5000/

2 threads and 100 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 144.82ms 161.45ms 976.32ms 79.36%

Req/Sec 584.56 144.55 1.15k 67.00%

34995 requests in 30.08s, 5.54MB read

Requests/sec: 1163.28

Transfer/sec: 188.58KB

With the same number of processes, gevent coroutines have allowed us to increase the number of requests per second we can handle by 20x. Not only can our server now serve more requests per second, it can support more concurrent connections with a lower latency. The bottleneck is now the CPUs ability to process all the requests, and the operating system’s capacity to handle large numbers of concurrent connections (which can be tuned).

➜ ~ wrk -t 2 -c 1000 -d 30 http://127.0.0.1:5000/

Running 30s test @ http://127.0.0.1:5000/

2 threads and 1000 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 197.11ms 396.31ms 1.98s 80.30%

Req/Sec 703.81 562.38 1.41k 46.07%

37680 requests in 30.05s, 5.97MB read

Socket errors: connect 749, read 0, write 0, timeout 5

Requests/sec: 1253.82

Transfer/sec: 203.26KB

We can still support more concurrent connections, albeit with increased number of socket errors.

To return to the original point of this post - If you are attempting to improve scalability of a legacy app, the key thing to do is to replace any synchronous, blocking i/o calls with an asynchronous alternative. In this simple example we have improved the number of requests per second by 100X, and the number of concurrent users we can support by 100X, all without any code changes.

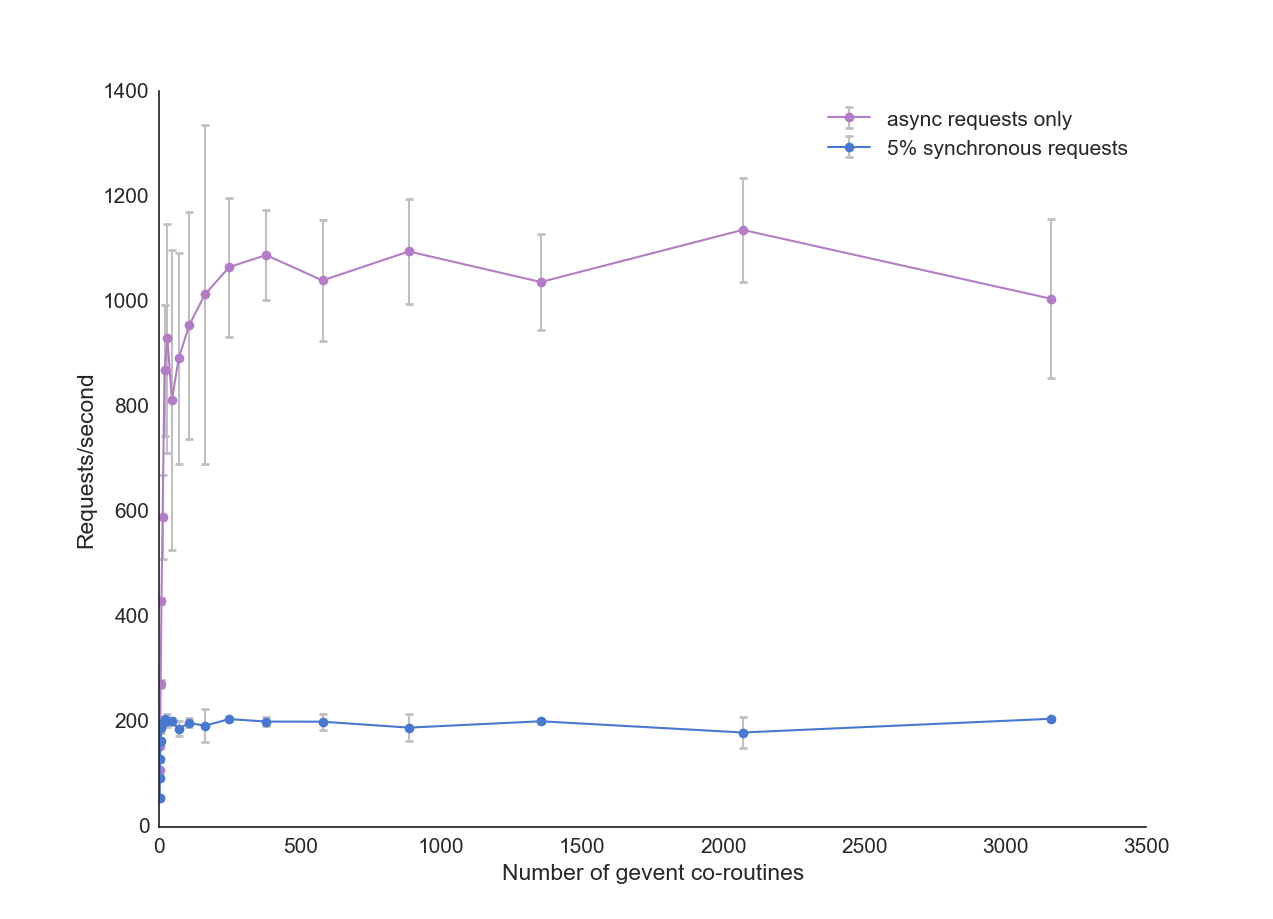

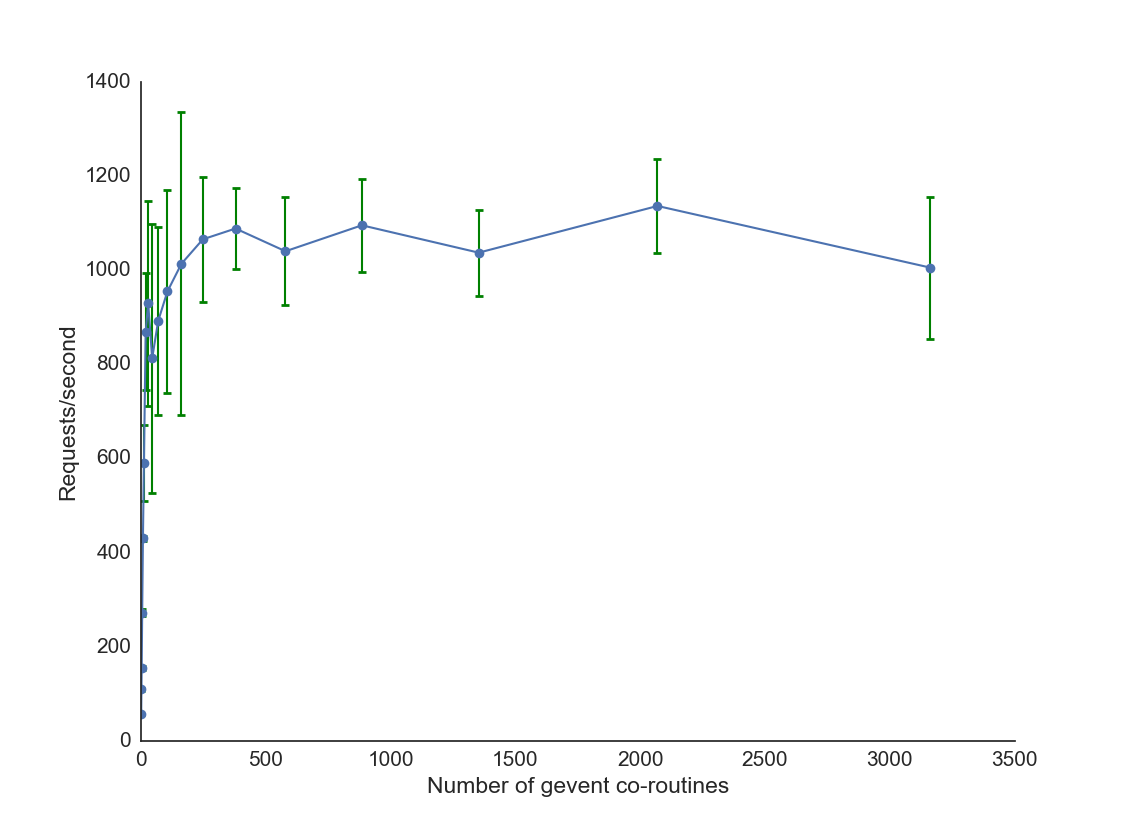

In a real app you may need to swap out your database library, or memcache/redis library in favour of something that is coroutine-aware, and will yield when waiting on i/o. An important thing to realise is that every i/o call must be asynchronous. If you refactor 99% of your code to be asynchronous, and leave just one blocking request, it will be in vain. Each time one of these requests happens, hundreds of coroutines will be paused while they wait for the one blocking request to complete. Updating our code:

@app.route("/oops")

def non_yielding_io_bound_request(min_response_time=0.1, mean_response_time=0.25, std_response_time=0.12):

io_call_time = np.random.lognormal(np.log(mean_response_time), std_response_time)

wait_time = min_response_time + io_call_time

get_original('time', 'sleep')(wait_time)

return "ok"

@app.route("/")

def make_requests(fraction_io_bound=0.2):

if random.random() > fraction_io_bound:

return cpu_bound_request()

else:

if random.random() > 0.25:

return io_bound_request()

else:

return non_yielding_io_bound_request()